A. Marshall Irving: The Man Behind The Beloved Stony Brook Eagle

February 16, 2021Marshall Irving was always fascinated with how things work.

You know the type. He can fix almost anything. And as the ‘Keeper of the Stony Brook Eagle’ atop the Federalist-style Post Office in Stony Brook, he’s the person responsible for making sure the clock works and the eagle’s wings flap every hour on the hour, as they’ve done since 1941, delighting visitors.

Starting at a young age, Irving was fascinated with taking things apart and putting them back together again. Fixing things and building things. And not just small things, like clocks and watches, which he taught himself to work on. When he was a boy, he took apart an old piano and rigged up parts to create a go-cart. He built his own kayak.

“I’ve always just been curious,” he said.

He went on to get a degree in steamship engineering from the prestigious Kings Point Merchant Marine Academy (he scored 10th in the country on his entrance exam) and received a master’s degree in engineering management from Long Island University (C.W. Post).

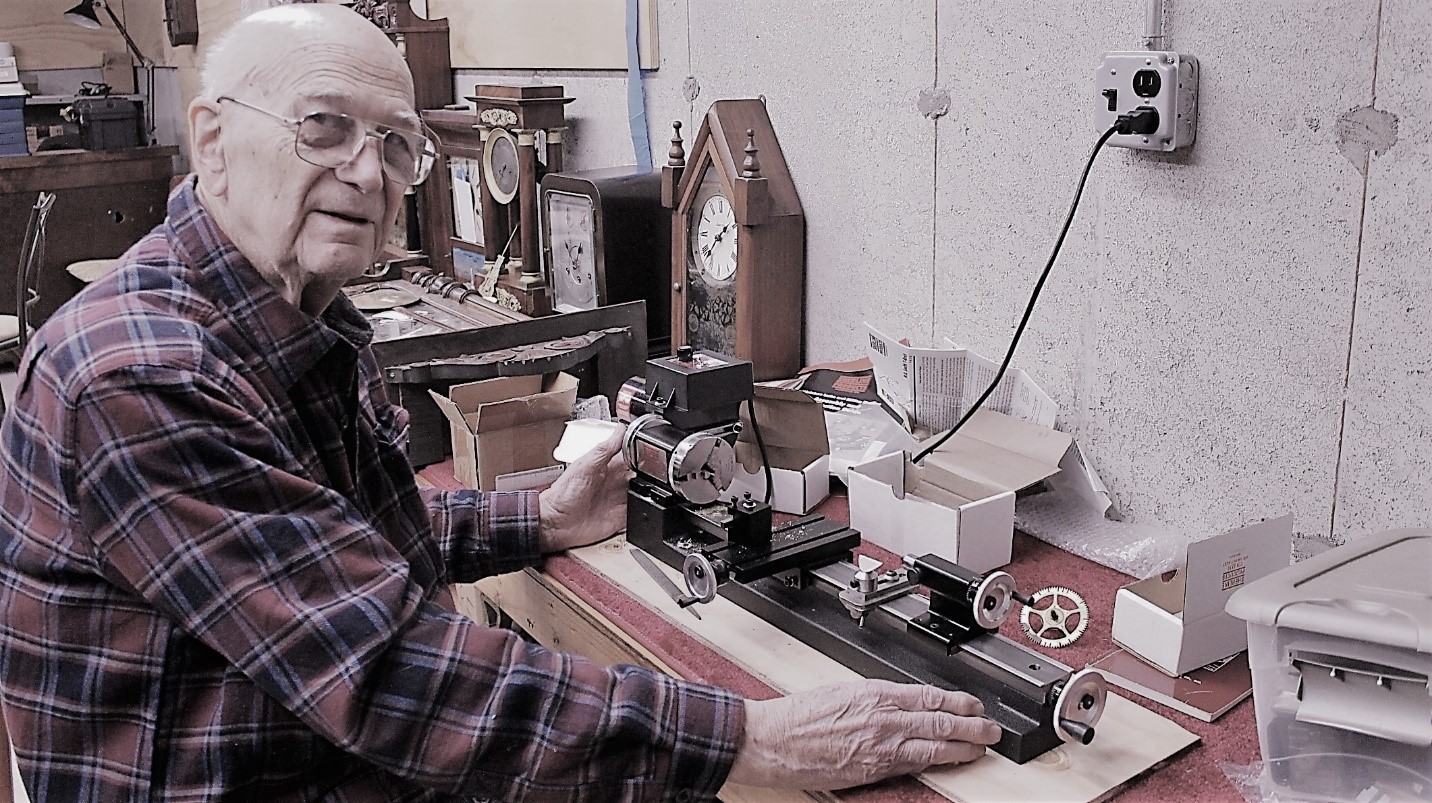

Today he is referred to as Antiquarian Horologist (dedicated to the study of antique clocks, watches and other forms of timekeeping). Turning 90 on Apr. 10th, 2019, Mr. Irving keeps active and engages in many activities (including clock repair and teaching clock repair), and he is warmly known for his care of Stony Brook’s iconic clock and eagle in the Harbor Crescent . The well-known eagle was dedicated by visionary philanthropist Ward Melville 78 years ago in the post office pediment. It has an impressive 20-ft wing span.

CENTERPIECE OF AN HISTORIC VILLAGE

The post office is the centerpiece of the Stony Brook Village Center, and was part of Ward and Dorothy Melville’s vision to create a “living Williamsburg.” Mr. Melville formed the Stony Brook Community Fund, now called the Ward Melville Heritage Organization (WMHO) in 1939 as a non-profit corporation. After gaining community approval in January of 1940, Ward Melville enlisted the help of close friend and architect Richard Haviland Smythe and created a crescent-shaped Village Center with connected shops grouped around the post office. The clock itself, beloved by locals and often called out as an must-see attraction by travel media, was built by Littlefield-Alger Signal Corp. of Rockville Center, NY.

The creation of the Village Center shops, completed in 1941, was initiated at Ward Melville’s own personal expense of $500,000, or in today’s conversion, over $8, 000,000. He relocated, demolished, or modified some thirty-five buildings in the downtown area. Two new business sections were completed in 1965 and 1987 in the same Colonial-style architecture. The center continues to draw visitors who come for the shopping and the seasonal events throughout the year. And they come to see the eagle.

Mr. Irving met the Melvilles when Mrs. Melville asked him to work on one of her clocks. It was a Dutch clock that had been in her family for generations.

“She was a very genteel woman, easy to get along with,” he said. “She really accomplished so much here. She treated me well and never complained.”

Keeping the Stony Brook clock and eagle functioning is a labor of love, according to Irving. Accessing it is another story. Getting up behind the eagle to work on it entails a couple of staircases, a pull-down ladder and a narrow catwalk. When he was first called in to work on the clock and eagle he retrofitted it to synch with a clock downstairs in the post office so workers could set the clock from the ground floor. He also added a push-button to flap the wings for special visitors.

At that time, the eagle hadn’t been working for probably twenty years. The gears were so badly worn that the building would shake, he said. “You could hear it from two blocks away.”

The challenge then, and now, is working with custom parts from the 1940s. He had to rebuild the original gear box since he couldn’t go to the local hardware store and buy a new one and he put in a chain drive and added a separate gear box. Recently, the drive motor to turn the hands stopped working and Mr. Irving was again called upon to craft a solution.

FROM A SMALL FARM TO NAVAL ENGINEER

Mr. Irving, who grew up on a family farm in Maryland, came to Long Island in 1947 to attend the Merchant Marine Academy after finishing polytechnic school in Baltimore. After receiving his degree he worked for 18 months with the United States line aboard the 400 foot, 10,000 ton SS America.

Mr. Irving, who grew up on a family farm in Maryland, came to Long Island in 1947 to attend the Merchant Marine Academy after finishing polytechnic school in Baltimore. After receiving his degree he worked for 18 months with the United States line aboard the 400 foot, 10,000 ton SS America.

Afterwards he went on to work for Sikorsky as a draftsman before settling in at Dayton T. Brown’s testing lab in Amityville working on aircraft and survival and safety gear for the U.S. Navy.

During the Korean War he was ordered to serve aboard the Intrepid as a lieutenant junior grade in Norfolk. In 1955-56 he was once again aboard the Intrepid, transporting special weapons through the Mediterranean during two deployments with the 6th Fleet mainstay to prevent Communist aggression in Europe and the Middle East.

Mr. Irving stayed in the Reserve for 25 years as lieutenant commander, while he continued to work at Dayton T. Brown for 20 years. He married his sweetheart, Arline, a beautiful woman who was a model at the time for Bonwit Teller. Interestingly, the two were a ‘cover couple’ for Journal magazine in May 1953 with several pages and photo spreads detailing their marriage, honeymoon and their home life in Fresh Meadows.

She said of her husband: “We just hit it off. I liked that he was involved with ships. My grandfather was a sailor.”

He said of his wife of 66 years: “She chose me. I was lucky I guess. She probably could’ve had her choice of millionaires.”

The Irvings, who moved to East Setauket in 1960, have four children (two boys and two girls), six grandchildren and two great grandchildren with another on the way. A son who lives nearby also has a keen interest in clocks and mechanical things.

BRUSHES WITH HISTORY

Over the years, Mr. Irving’s had many adventures. While scuba diving in France, he and some other crew member friends were anchored near a private beach. Several ‘suits’ came down to ask who they were and what they were doing. Apparently, the beach was a getaway for Joe Kennedy who proceeded to come down and meet them.

Another time during his tenure with the naval reserve, Mr. Irving was assigned to debrief “special guests of the ‘Hanoi Hilton’” (Vietnam prisoners of war) in Bethesda, he said. Among the former U.S. prisoners who were brought in was John McCain. While he didn’t debrief him directly, he was responsible for reading the reports.

“He was a real hero,” Mr. Irving said.

Through the years, Mr. Irving continued to tinker with and fix clocks and other mechanical devices. When asked which of the clocks he’s worked on over the years was his favorite, he told the story of a clock that had a link back to the French Revolution.

An acquaintance out east asked him to work on what appeared to be a King Louis XIV clock that had an exquisite case carved with the likenesses of ‘the three fates.” The man told him that he thought it might have been stolen during the French Revolution, and it ended up in his grandparents’ house in Brooklyn after his grandfather did a paint job, and the client paid him with the clock.

The clock was passed down to the gentleman and when he contacted Mr. Irving to fix it, he asked him to try to find out more about its history and said he would gladly return it to Versailles if they could prove it was theirs.

Mr. Irving found out the clock was indeed valuable. The cabinet was created by André-Charles , a famous French cabinetmaker and inlay artist known as the “furniture jeweler.” (1642-1732). Mr. Irving worked on the clock, took pictures of it, wrote about it and submitted the story to the National Watch and Clock Museum in PA. After a correspondence with the French government, they responded by saying that they had one just like it, but that one was not theirs. The gentleman got to keep his clock with a clear conscience.

Mr. Irving also worked on the Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan, which he described as “a beautiful mechanism run by three-story tall weights, 175 ft. up in the air.”

MAYBE IT’S ‘IN THE GENES’

Another favorite is the clock passed down to him from his grandfather. His grandfather was a librarian for the B &O Railroad (the Baltimore and Ohio railroad was the public carrier rail in the U .S.) and the clock had been in his office.

.S.) and the clock had been in his office.

Mr. Irving’s great grandfather (on his grandmother’s side) was said to be an ‘uhrmacher’ (clockmaker) in Germany, but neither of his parents were mechanically inclined. He said he had cousins who were machinists and mechanics and they helped him work on cars and bikes.

Today, approaching 90 years old, Mr. Irving maintains a workshop in his basement, where he still regularly fixes clocks and watches. He also established a clock school, where people can learn to fix clocks and watches.

Clocks are his passion, he said. “Maybe it’s something in the genes.

– By Kristen Matejka